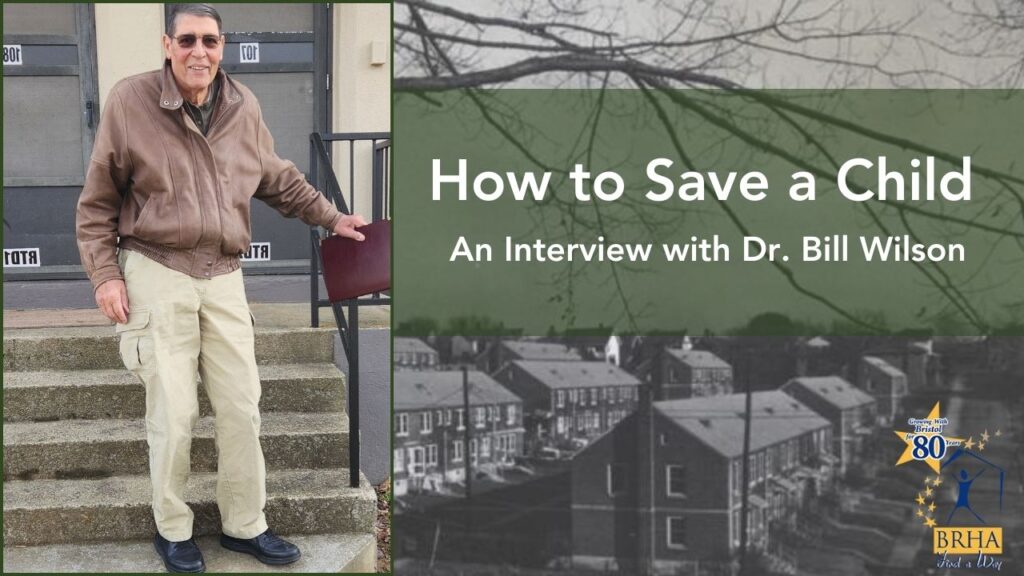

Dr. Bill Wilson is a well-loved teacher and administrator to many past students from Sullivan East High School, located in Bluff City, Tennessee. He was born in 1943 in Bristol, Virginia. The following interview, linked below recounts his life as an impoverished child, who once lived in Rice Terrace apartments, public housing managed by the Bristol Redevelopment & Housing Authority (BRHA). He tells of the hardships his family faced and the comfort they found in their Rice Terrace apartment. He has presented this story to teachers and administrators many times to show them that every child counts, no matter the circumstance. The lessons he learned as a child carried him on to be a compassionate, unwavering, yet stern educator.

How to Save a Child, Transcribed

Interview with Mr. Bill Wilson

Interviewed by Rachel Armor

January 30, 2024

Bristol, Virginia

Introduction from the Interviewer, Rachel Armor

Mr. Bill Wilson is a well-loved teacher and administrator to many past students from Sullivan East High School, located in Bluff City, Tennessee. He was born in 1943 in Bristol, Virginia. The following interview recounts his life as an impoverished child, who once lived in Rice Terrace apartments, public housing managed by the Bristol Redevelopment & Housing Authority (BRHA). He tells of the hardships his family faced and the comfort they found in their Rice Terrace apartment. He has presented this story to teachers and administrators many times to show them that every child counts, no matter the circumstance. The lessons he learned as a child carried him on to be a compassionate, unwavering, yet stern educator.

Few edits have been made to the following narrative. You will see my notes as the interviewer in parentheses.

Rachel Armor

Story Title:

How to Save a Child, by Bill Wilson

Bill Wilson

(I met Mr. Wilson in the parking lot of the BRHA. He began his story there. The recording started once we were seated in an interview room in the BRHA EnVision Center.)

I talk with school administrators, school systems, teachers, staff, teaching staff, and so forth. I started out by saying, this is not so much about me as it is about those people who literally picked me up on their shoulders and carried me forward in life and made an impact on me. And did the number one thing that I think is so important in life. They believed in me. They believed in me. And it’s so important to have someone to believe in you. The question I ask to them now is, where do you think shooters come from? Well, see, I happen to know through study where shooters come from. They come from the school they’re going to 90% of the time.

And they pick up an evil seed of not fitting in socially inept, and economically disparate. Sometimes single parents, sometimes no parents, sometimes a grandparent. And that seed continues to grow. And they end up in life with two choices commit suicide or go, go get even. And we get the information on getting even through the reports that media brings us without studying the child. My encouragement to them is and I’ve got a daughter that’s a school administrator, by the way, and it’s in a middle school. And she oddly enough, talked to me yesterday about a child she’s interested in. That’s so much fits into that category right now as a sixth grader. And what he needs is somebody to love him and somebody to believe in him. And so that’s not part of my story, but it is part of my story. And as much as I’m a rescue child. And you will see, I think, in this story that I’m going to start way back where my mother came from.

She was 100 percent full-blood Cherokee Indian. And they were tenant farmers, and they were really saved from the Trail of Tears, her parents, by farmers who they work for in western North Carolina. So, they migrated out of western North Carolina farm by farm by farm. She lost her mother, her father, her grandmother, her grandfather. And she was left at the age of 13 to raise her little brother. She struggled until she was 15 years old. She was born in 1920. And she met my father somewhere near Rogersville. He was a trucker. And he was born and raised just off Euclid (Euclid Ave, Bristol VA) right here up the alley off Euclid. His mama was a fortune teller. His daddy was a saw sharpener. They both sold booze. And he became a booze hauler, and a seller of fruit and vegetables and so forth. He worked in a lot of different ways. He was a very stern physical specimen. He was about the height of me (over 6ft tall) and born in 1910. Very large for his age. And a handful when they come to arrest him. The rule was, don’t just come by yourself, bring a carload. So, mom came out of Western North Carolina with her parents. They met when she was 15. By the time she was 16 in May, she had my brother in August of 1936 at the age of 16. My two sisters were born before I came into the world and in 1943, she brought me into the world. My dad was by all accounts a stern figure. I didn’t get to know him that well because he was killed by the time, I was five. But I know he was a loving father. The story I can remember best about him is he sat me on one knee and a dog on the other, a little cocker spaniel. Feeding both of us candy. He swatted my rear end a couple of times when I stole chew tobacco off of him. I thought it was candy. Oh, and it was running down my chest. He swatted my hind end and kept me out of his chewed tobacco.

But I’ll tell you then about his dad. He had a friend Charlie that was in prison. They had run together apparently through childhood and so forth. And Charlie got into trouble and got in prison. His family came to my dad by the name, my dad was Cairo Wilson, George Cairo Wilson. My granddaddy was George. And my grandmother, like I say, she was more like a carnival character. She was a little bitty thing. Ginsey was her name. And she had the crystal ball and everything. She actually took a ward off of my finger. I had a great big seed board right there. My mother said, well we’ll go over to grandma’s, and she’ll take that wart off of you. Oh, I began to holler and cry and cry. “She ain’t going to take that wart off of me. No, no, no, no. She’s not going to do that.” We got there. She sent me out in the alley. The driveway was rock and gravel then. She said pick me up three smooths of gravel. And bring them back to me. Well, when I did, she had a tattered cloth about that big (the size of his palm). And she took them stones and did a seance over mine. And rubbed them stones one at a time, “Eeeeiooo, eeeiooo.” And I said, what in the world is she saying? Three of them. She put them in that, tied the corners. And said, “Young man, when those stones escape that cloth, your wart will fall off.” I went home with the wart on my hand. Weeks later, I began to see it going around the edge. It was making a line around the edge of it. And I went and showed mom. And she said, “Your warts going to fall off.” Those stones are about the size of that cloth. By gosh, in about two weeks, the wart fell off. And to this day, I’m saying, wait a minute here. But rich people would come and drive up the alley and park and get their fortune told. She made all kinds of medicinal stuff.

My mother was an Indian medicine woman. Her parents were Indian. Her grandmothers were medicine women in the Cherokee tribe. And she could go through the fields and pick out every weed or every plant there was that could be medicinally developed to help. Indians never had no medicine. Whatever they had, they made their own. And I guess some of them died early. But she could do that and did do it. Eventually, she raised nine kids. We were four, and my stepfather had five. But anyway, back to Charlie. He broke out of prison in a snowstorm in 1948. And his family came to my dad and said, “Charlie said you would know where he was. If he broke out of prison, he is broken out of prison. Do you think you know where he is?” My dad said, for whatever reason, “Yeah, I think I do.” So he went into the mountains, found Charlie, got him out, hid him out, the law found out, come and arrested him. Well, in an over-exuberant interrogation, with him resisting probably, I don’t know that to be a fact, but probably, based on what I know about his nature that my mother told me and friends shared and so forth. But anyway, over-exuberant interrogation, they fractured his skull. And his cellmate was turned loose on good behavior, and they sent him to tell my granddaddy that Cairo was killed. He said that when they drug him back to the cell, they threw him in place down, and he never moved. Bristol did nothing about it. And we hold no grudges. As a matter of fact, I’ve got two nephews. One is deceased now, but he was with Sullivan County Sheriff’s Department as an officer. One of their elite special forces officers. And I’ve got another one that’s currently an investigator for Sullivan County. And I’ve got a grandson that worked for Sullivan County. We don’t hold no grudges against police. I was scared to death of them when I was a little boy. I mean, totally, totally scared to death. Frank Thrash helped me get over that, while I was living in Rice Terrace, he helped me get over that.

But my grandparents, grandfather, and grandmother, both said to my mother, “You’ll never raise those kids. Put them in an orphanage. And go live your life. You can’t raise them. You can’t drive. You’ve got no education.” She actually had an eighth-grade education. And very smart. Well-read and really, really sharp. But she said, they said, go live your life. She said, and she told me one time, I said, “What did you tell them when they said that?” She said, “I told them you guys were my life.” And we were. She worked sometimes at two jobs. I’ve seen her go out in the snow in sandals from right over here (points to Rice Terrace apartments). And we moved a lot. We moved out of Rice Terrace a couple of times and then moved back. And one of the places was up on the hill there, and I can’t tell you what the, I can take you to the apartment, but I can’t tell you what number it is. I remember coming around as a boy and sitting on the rail right over here (pointing to the old rail-line across the street). It’s still there. I also remember taking a makeshift bicycle and riding down the road and going down there to the filling station. There used to be one down there. And an 18-wheeler come down over the hill and hit the back of that bicycle and knocked me 20 feet in against the gas pumps. And I thought I was dead. It knocked me out. But it skinned me up, never broke no bones. It skinned me up. Probably, the good Lord saved my life. That’s all. That’s the only thing I know. But anyways, we lived there. And like I said, I was scared to death of men, particularly police officers. And I wouldn’t go to the Boys Club (possibly located where the Boys & Girls Club is today). My brother talked me into going over there one time, and I seen Frank Thrash and seen how big he was. He was a monstrous man. Oh, he’s a man’s man to me. You can imagine me at five, six years old, me looking up at him. But anyway, my mom got to Mr. Thrash and said, “My son is scared of you, and he’s scared of Boys Club. He’s just scared of men. We’ve got to find a way to get him through all this.” Well, he came over one day, came over to the apartment, knocked on the door. And I heard him say to my mom, “I’ve locked my keys inside the Boys Club, and I can’t get to them. I wonder if little Billy would come, and I’ll take him on my shoulders, and walk him across the street.” And he put me through a back window. I unlocked the front door, and he came in and got his keys, put me on his shoulders, and carried me back. And I thought, gee whiz, he’s a pretty nice guy. I remember holding onto his head. So, they got me into the Boys Club, and I got more used to him. And he watched over me just like he was my daddy. I mean, he was a tremendous guy. He was a boxer. Taught my brother how to box. And my brother became a Navy boxer. Competitive, exhibitionist Navy boxer. And my goodness, he could throw a punch. But I learned to live with the other half, you know, that I viewed as killed my daddy. And I slipped off the house where we lived up here on the hill, and I wanted to find my brother at Virginia High. And I got lost. Well, I finally, somebody pointed Virginia High out, and I told them what I wanted. And, of course, they called the law, and the law come to get me and take me back home, and I thought they was going to arrest me. So, from the back seat, I said, I remember asking them, “Are you going to kill me?” And one of them looked around startled and said, “What would make you think that?” I said, “You killed my dad.” They didn’t kill my dad. Another box did. But the life and times of a kid, it’s, we moved out of Rice Terrace finally when I was 11 years old. And my mother married my stepfather, who was an old-fashioned, hard-nosed logger. He had a logging camp, a sawmill, and a farm. And his boys, he had four boys and a girl, and mom had two boys and two girls, and they had nine of us. And the older ones were moving away by the time I was 13. I was a pretty good-sized kid when I was 13. And I ended up having to do a man’s work. Me and my stepbrother were the only two left. We ended up having 40 milk cows. We put up 5,000 bales of hay a summer. We sawed in a sawmill. We loaded logs by hand. I pulled them out with a horse, offloaded them, sawed up the slab boards that come off the logs, sawed them up for wood. We loaded a 2 1⁄2-ton flatbed with sideboards on it and took it to whoever wanted to burn it for $12 a load. And I learned to drive that 2 1⁄2-ton truck when I was 13. They didn’t have much law on gravel roads down in Rocky Springs. It just wasn’t there. And I was a big kid. They never did stop me, but I learned to drive very early.

(Rachel Armor)

Where is Rocky Springs?

(Bill Wilson)

Rocky Springs is between Blountville (TN) and Piney Flats (TN). It’s about halfway between Blountville and Piney Flats, and I went to a little three-room school for a short time. It had no water and no plumbing. We went outside to get a drink of water. We went outside to use toilets. You had to go outside to get to the cafeteria. It was amazing. Three teachers, three rooms, three teachers, six grades. And I spent a short time there. I went to Mary Hughes, an eighth grader, and played eighth-grade basketball. And the following year, well, actually, it’s kind of a little bit of a story. My stepfather said, “You’re not playing basketball.” And it tore me up because I played eighth-grade ball, and it didn’t interfere with milking. And we had to milk twice a day. We got up at 4:30 in the morning to milk cows. And sometimes I’d get in and off a basketball trip when I was a high schooler. We’d get up maybe 12:30, or 1 o’clock in the morning for a road trip. I still had to get up 4:30 to milk cows. And my coach would let me sleep in a dressing room down in his office, and he’d wake me up for a couple of classes, and I’d just miss a couple of classes. But they took care of me and fed me. But, you know, my stepdad said when I was an eighth grader, I told my mom, I said, Coach Mason wants me to practice with him in the summertime. I said, “Mom, I think he’s going to move me up on the varsity as a freshman”. And my stepdad said, “No, you’re not playing. I need you here to work.” And so, I went and told Coach Mason. I said, “I don’t think he’s going to let me do that. I don’t think he’s going to let me play, Coach.” He said, “I’ll come over and see him.” So here he come. They were sitting on the front porch talking. And he said, Coach said, “Mr. King, you need to let this boy play basketball. He could get a scholarship.” But my stepdaddy had a third-grade education. He said, “What’s a scholarship?” He said, “That’s where the school sends him there free and feeds him and houses him and gives him his education.” He said, “He don’t need no education. He needs to learn how to work.” I said, “Gosh, I already know how to work. I’ve been doing that for a long time.” But anyway, my mom was standing just inside the screen door. I didn’t see her. My stepdaddy didn’t see her. My coach didn’t see her. She didn’t want to embarrass my stepfather. So, when my coach pulled out, she came out and walked over in front of my stepdaddy and said, “I’ve got a question for you that you need to answer right now on the spot. Does he play basketball, us living here, or does he play basketball, us living somewhere else?” He looked up at her, startled. She intended to leave him if he cut me out from basketball. Her kids were still the most important thing in her life. And he said, “Well, OK, we’ll let him play.” Well, they did and I played four years on the varsity. And then as a junior, I started getting some interest from colleges. Kentucky come and watch me play. Tennessee come and watch me play. Maryland come and watch me play. Middle Tennessee, ETSU, Milligan. I had about, I don’t know, 10 or 12 schools. I chose Tennessee. So, in 1962, I went to the University of Tennessee and played on the freshman team. When freshmen had to play freshman ball, I started on the freshman team at UT. And Coach Mears came in that year as head coach. And he had a style of basketball, pitter-patter basketball, I call it. Slow down, slow down, slow down. My gosh, in high school, we scored over 100 points 9 or 10 times, run and gun. And I said this is killing me. I was disillusioned, really bothered. So, I quit Tennessee. Came and played ball for ETSU. Was captain of the 1966 team and started all three years and got a BS degree. Came back and coached at State. And after coaching in high school, came back and coached there, got a master’s degree. And then got 45 hours, all the academic courses I needed for a doctor’s degree.

And many, many, many was the time down that trail that I look back and actually missed Rice Terrace. The comfort, the time that solved some issues in terms of my fears and my circumstances. I had diphtheria when we lived up here and we got quarantined for two weeks and the church fed us. I almost died. A time when we didn’t live in Rice Terrace, about a six-month period, I was playing along the creek with some boys, and they shoved me in. And rather than fall straight flat, I jumped in, and I come down on a fruit jar on my left foot. I got gangrene in my left leg. And I heard the doctor say to my mother, if that red streak has not started disappearing, we’re going to have to take his leg off in the morning. I was absolutely just never slept a wink. I was shocked out of my mind. I’m going to lose my leg, Mama. She said, no, you’re not either. And I didn’t. I seemed to get all kinds of problems. I got my hand hung in a barn hay fork pulley. About 1,000 pounds of hay, two horses pulling it. And I was letting the rope come through my hand and it jerked me down between the pulley and the rope. And about ground my thumb off and broke my finger, this finger, this finger, this one, my thumb, that one, and this one (his entire hand). And I’ve broken this one in basketball and that one in a hunting accident. The only two that haven’t broken is these two. I’ve had 15 broken bones and 16 surgeries. I’ve got two metal knees and two metal shoulders. But you know what? I’m vertical. I’m upright breathing. Bless the Lord. Nobody really knows unless I tell them about that. That’s the adverse sides.

My mom had more adversity in her life than you could write on pages. She lost both parents, both grandparents. She lost her husband. And at the age of 51, she passed away of pneumonia. But she was like a saint on earth. She was incredible. She was one of the most beautiful women I ever seen in my life. She had long black hair like you do and high cheekbones with a complexion about like mine. And when we were living over here, I was playing cowboy and Indians with one of my little buddies down, on down the line down there somewhere about four apartments down. His mother came to the door and said, Jimmy, you get in here. You can’t play with that little nigger. Oh, it broke my heart. I just thought, what’s a nigger? I never even thought about a nigger being black and, you know, being spurned like that. Well, I went home and cried. My mother happened to be there. And she said, here, come go with me. We went back down there. She knocked on the door. When the lady come to the door, she said, I have you know that my son is not a nigger. He is a Cherokee Indian. And if he was a nigger, your boy is not too good to play with him. And the next time you refer to my son in such a harsh way, there’s going to be a hair pulling and I’m going to be here. She just threatened her. Well, me and Jimmy got to play again. That stopped that.

So, I went on to college. I played with Tennessee. I played with ETSU. I got a BS and a master’s. I got 45 hours toward a doctor’s degree. I met my wife in 1965. Beautiful, registered nurse, sharp girl. She’s about this tall (showing her height – about half of his). Little, she weighed 110. She weighed 110 and I weighed 220. We got married. We eloped and went to, well, I still play in the state, went to Gate City, and eloped and got married. If you got married with a scholarship, you lost your scholarship. So, I said, I’ll risk it. And my last year of college, we were married. My coach called me in, Coach Madison Brooks at state, and said, “Well, chief, I heard you got married.” I said, “Oh my gosh.” He said, “Why in the world did you do that?” He said, “You went over there, and he eloped and me, and my wife were going to give you a wedding.” I said, “You’re kidding, coach.” He said, “She works with my sister-in-law at VA. We knew that you were going to get married, and we knew when you got married.” I said, “Oh my goodness.” He said, “I was waiting for you to tell me.” And he said, “It’s perfectly all right. We wouldn’t lose you under no circumstance.” I thought, man, it’s people that believe in you, people that really do. And so, we got married. We bought us a trailer. We lived in the trailer, married couples trailer park at ETSU for a year. Then we moved to Elizabethton (TN), and she went to Johnson City (TN) and I went to Johnson County (TN) to coach in my first job. The following year I went to Sullivan East (Sullivan County, TN) and I coached there for about 16 years. I coached at State. Then I finished the direction of a doctor’s degree and got an administrative job. And I was a school administrator for 17 years. I retired as principal at Sullivan East in 2001 and got myself a job in security and worked as a security supervisor for Aerojet Rocketdyne for 10 years.

She was my high school English teacher. And I loved Nell Starnes. When we had a road trip going like to, let’s say, we were going down to Lamar or we were going up to Hampton or someplace like that, she would say during the day, she said, “Where are you going to eat supper?” And I said, “Ms. Starnes, I probably will do it at home tonight about 11 o’clock.” And she said, “No, you won’t. You’re coming over. My mama’s going to cook for you.” And she’d take me home with her, and they’d feed me, and she’d get me back in time to catch the bus, and I’d go play. And so, I was coming down the hall one day, and she said, I think probably a senior year, “Come here, come here, Bill.” I went down there like a little puppy dog, and she said, “Sit down right there.” I just sat down like whatever she wants is what she gets. She said, “I’ve been hearing what they’re saying about you.” And I said, “What are they saying about me, Ms. Starnes?” She said, “Why, you couldn’t pass college courses. You couldn’t pass out the door.” I thought everything over a “D” was wasted in high school. I was a big reader. I read a lot. She asked me to read a dictionary, and I read a dictionary. I read it every page. And she said, “I think it’ll help you. You’re good with vocabulary.” She’d make me stand up and give speeches in the classroom. She had me teaching Shakespeare, of all things. And so, I, she said, “I’m here to tell you, their lying!” She had a master’s degree from Columbia University. Sharp woman. Back when women didn’t necessarily go to that level. She said, “You can pass. I know you can pass. I know that you can get a college degree. And when you do, it’ll mean” …this and this and this and this. She went through the whole thing. I went running up the driveway when I got home off the bus, and I said, “Mama, Ms. Starnes said she thought I could pass in college.” She said, “You can.” Somebody who believed in me again. Somebody. So, I went on, and I talked with her at East. And then I became an administrator. And the day that I was going to be introduced to the staff, she came around the corner of the A circle, into that little place right there in front of the library. And she put the brakes on, put her hands on her hip, and just stood there and looked at me. And looked and looked. And I was uncomfortable. She looks a lot. And finally, she said, “I told you so.” And I said, “Yes, ma’am, you did.” And I thought of it many times while I was there and there making the effort trying to get there. I do remember that. And I said, “By the way, I made Dean’s List in a master’s degree.” She said, “I thought you could.” And yes, it counted so much that somebody thought I could. And that’s just another example of those things. And you know, it started right across the street. It started right across the street (pointing at Rice Terrace). And I’ve shared with a lot of people my experiences at Rice Terrace. Rice Terrace don’t condemn you to poverty. It does not condemn you to failure. It does not condemn you to ill-treatment. It should encourage you to establish goals and have ambitions because you can reach them. You can do it. If anybody, I had a girl that I dated for a long time. And we still really are great friends. And she said, “I have said many times, if Bill Wilson could do what he done, anybody could do it.” And I said, “Well, you’re right!” Because I come from nowhere. I’m a rescued child. I’m a rescued child.